13 June 1917

- Neil Datson

- Sep 19, 2023

- 6 min read

Updated: Oct 31, 2023

(This is the first chapter taken from Neil Datson's The British Air Power Delusion 1906-1941)

On 13 June 1917 seventeen German aircraft flew over London and dropped seventy-two bombs on the city. In all 162 people were killed and over 430 injured, making it the worst air raid of the war. One especially momentous bomb fell on Upper North Street School, Poplar, in the modern Borough of Tower Hamlets and little more than half a mile north of Canary Wharf. Rather than exploding on impact it broke into two pieces when it hit the building’s roof. One piece fell through three floors, killing two children on its way down, and exploded in the basement where there was a kindergarten class of sixty-four children in progress. Sixteen were killed and more than twice as many injured. Only two of the victims were more than five years old. A soldier who was one of the first to arrive on the scene related:

‘Many of the little ones were lying across their desks, apparently dead, and with terrible wounds on heads and limbs, and scores of others were writhing with pain and moaning piteously in their terror and suffering.

‘Many bodies were mutilated, but our first thought was to get at the injured and have them cared for. We took them gently in our arms and laid them out against a wall under a shed.’[i]

Jack Brown, one of the surviving children, later recalled that the following day was the first time that he saw a grown man cry, when the school’s headmaster broke down as he read out the register.

No less than ninety-two British aircraft, from both the Royal Flying Corps and the Royal Naval Air Service, took off in a vain attempt to intercept the bombers. Their efforts were piecemeal and ineffective. Although the sky was clear and the raiders could be seen from many miles away few of them got close enough to open fire. One that did was a two seat Bristol Fighter from No 35 Training Squadron. The volume of the Germans’ defensive fire was such that the pilot was compelled to abort his attack, his observer slumped dead in the seat behind him.

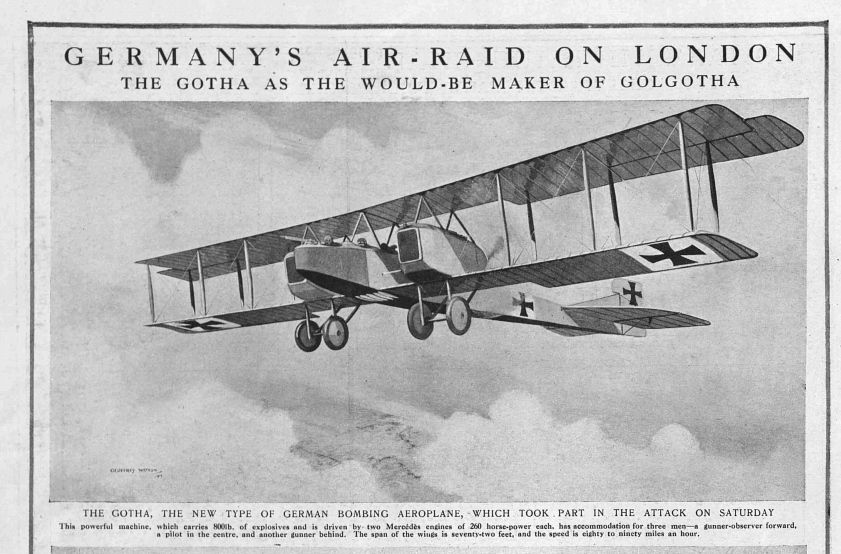

The attack was the first time that London was visited by Gotha GIVs, a type of aeroplane that first flew late in 1916. The GIV, the first Gotha model that was considered worth building in quantity, was a remarkable and innovative machine. It had a wingspan of nearly eighty feet and, when used on daylight operations, could carry a bomb load of 700 lbs up to a height of more than 16,000 feet. To enable the crew of three to function in the intense cold and thin air of such altitudes they were supplied with flying suits which had electrical heating elements woven into their fabric, and supplementary oxygen cylinders from which they could inhale direct through breathing tubes. The aircrews were somewhat ambivalent about the oxygen as it produced an unpleasant dry sensation in their throats. One pilot later wrote: ‘We rather preferred to restore our body warmth and energy with an occasional gulp of cognac.’[ii] The low temperatures frequently caused machine guns to freeze and jam, so the GIV’s defensive armament was also kept warm by electric heating. On night missions they operated at lower altitudes but carried a greater load of bombs. Their two engines were a new Mercedes type, each developing 260 hp, and built in right-hand and left-hand versions so that the machine’s airscrews would balance each other, ensuring stable flight characteristics. To help safeguard the lives of the crew, should they be compelled to ditch in the sea, the GIV was equipped with flotation bags and other aids that could keep them afloat for up to eight hours. Altogether, the GIVs fully merited the soubriquet bestowed on them by one French commentator: ‘les grands oiseaux de morts’.[iii]

The Gothas were operated by a squadron with the curious title of the Ostend Carrier Pigeon Detachment. Commanded in the air by Hauptmann Ernst Brandenburg, the squadron was specially trained as well as equipped, and tasked with carrying out disciplined, close formation, raids on targets in enemy territory – although in context ‘targets’ is scarcely the right word. At the time accurate bombing could only be carried out at very low altitudes. The closest that any air force came to hitting particular targets was to drop their bombs in something like the right area of a large city like London. For many airmen finding smaller cities at all was frequently too great a challenge. The Carrier Pigeons certainly didn’t set out with the intention of killing children, but to damage the London docks and other strategically important infrastructure. In the account given in the official British history Brandenburg reported to his superiors on what he claimed was a successful mission:

‘Our aircraft circled round and dropped their bombs with no hurry or trouble. According to our observation, a station in the City, and a Thames bridge, probably Tower Bridge, were hit. Of all our bombs it can be said that the majority fell among the docks, and among the city warehouses. The effect must have been great.’[iv]

13 June 1917 was the third occasion on which the Carrier Pigeon’s machines attacked the British mainland. On 25 May they had set out for London but had been compelled by the weather conditions to divert to towns on the Kent coast. A second attempt on 5 June got as far as Sheerness.

The little victims of the bombing were buried a week later in a common grave in a London cemetery. The crowd of mourners was possibly the largest and the funeral cortège the grandest ever seen in East London. The service was conducted by the Bishop of London and attended by government representatives. A message of condolence from King George V and Queen Mary was read out. Hardly surprisingly, the public were not placated by evidence of official or even royal concern. There was widespread anger; the authorities were blamed for their failure to protect the people and for their passivity in leaving German cities unmolested by British aircraft. The reputation of the RFC and the RNAS fell away; some airmen were even attacked in the streets. In the House of Commons the Member for East Hertfordshire, Noel Pemberton Billing, demanded an adjournment debate to discuss the raids. The nation’s most popular newspaper, the Daily Mail, demanded that the Germans should be repaid in the same coin:

‘The true defence lies in the most violent and sustained offensive through the air, attacking the German air stations and towns, not at long intervals but continually.’[v]

A few months later Pemberton Billing and the Daily Mail were to get their way. The cruel slaughter of the toddlers in Upper North Street School on 13 June was to lead – very nearly directly – to the greatest blunder in the history of British defence policy: the establishment of the Royal Air Force.

The damage done by splitting off a third service from the army and navy was not noticed at the time. Rather, its advocates claimed immediate - and total - success. In the 1920s Britain's traditional strategic policy was thrown aside in favour of a speculative theory for which there were no sounder foundations than newspaper speculations and mass popularity. The harms done were inexorable. By the mid-1930s faith in the RAF's theory of war was leading Britain's rearmament and even her foreign policy; misplaced trust in it underwrote Appeasement. Far worse, when the fighting started Britain's war effort failed because the nation's forces were badly divided, and they were directed by men who were every bit as deluded about modern warfare as the man in the street. In both blood and treasure the nation paid a heavy price.

[i] ‘German Airmen Kill 97, Hurt 437 in London Raid.’ New York Times, 14 June 1917.

[ii] Kurt Küppers to Fredette, 2 May 1965. Raymond H Fredette. The First Battle of Britain 1917-1918 and the Birth of the Royal Air Force, p 41.

[iii] Marcel Poëte. Barry D Powers. Strategy Without Slide-Rule, p 53.

[iv] Ernst Brandenburg. Sir Walter Raleigh and Henry A Jones. The War in the Air, vol 5, p 28. The War in the Air was published through the 1920s and 1930s in six volumes of narrative text and one of appendices. Walter Raleigh, really a Cambridge ‘man of letters’ rather than historian, was commissioned by the Air Ministry to write it. He died in 1922 and the task was handed over to the civil servant Henry Jones.

[v] ‘Again, No Warning! The Air Raid on the City of London.’ Daily Mail, 14 June 1917.